THE LARGEST POLAR EXPEDITION IN HISTORY

By: Laura Millan Lombrana/Anna Shiryaevskaya/Dina Khrennikova/Olga Tanas/Mira Rojanasakul

Photo: Alfred Wegner Institut/TASS

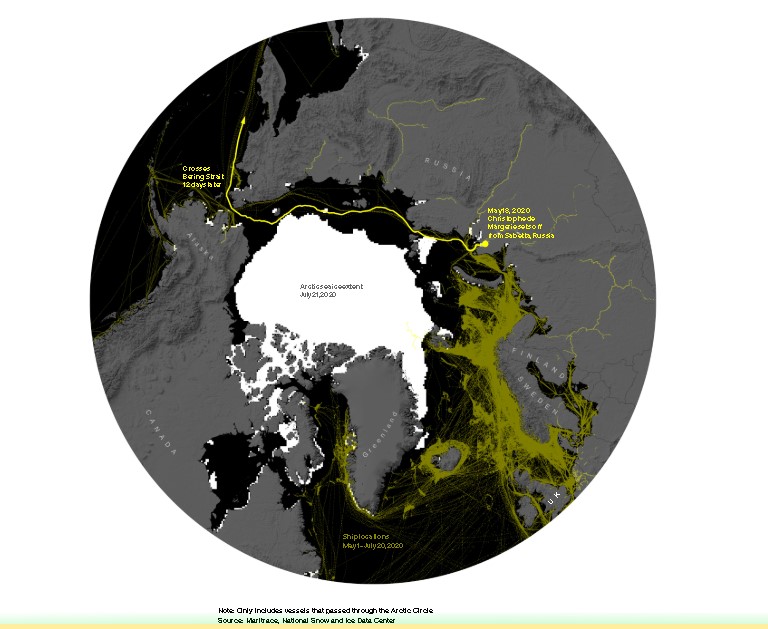

On a sparkling day on May 18, the nearly 300-meter-long tanker Christophe de Margerie set sail from the northern Russian port of Sabetta. Crossing the so-called Northern Sea Route in the Arctic waters, in just under three weeks it moored at the Chinese port of Yangkou, unloading its shipment of liquefied natural gas.

That relatively routine journey has now entered the record books: the earliest date a cargo ship took what’s usually an ice-blocked route. It’s yet another sign of how climate change is shrinking the Arctic.

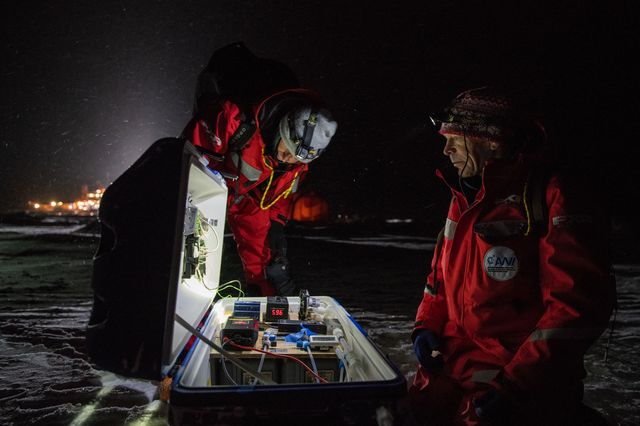

Around the same time the gas reached port, a ship called the Polarstern was also sailing in Arctic waters. But it was loaded with about 100 climate scientists from some 20 countries engaged in an exhaustive, year-long examination of the warming environment. To put it another way, the crew of the scientific ship is trying to understand why the tanker was able to leave so early in the season and what it means for the future of the planet.

The Arctic is rich in natural resources like fossil fuel and already under significant climate stress, warming more than twice as fast as the rest of the planet. The more the Arctic warms and melts, the more humans build industrial infrastructure, mine metals and produce oil and gas–emitting greenhouse gases that accelerate the warming and melting.

The two vessels tell the tale of a tug of war now playing out in Earth’s last frontier. One is looking for clues to climate change, and the other is racing to exploit that change for financial profit. It’s another kind of feedback loop, with ships passing in melting waters.

Unlike other areas of the planet, the Arctic is so inaccessible that there’s very little data to predict with precision how the ice cap will change under rapid warming. Researchers on the Polarstern’s MOSAiC mission—the largest polar expedition in history and the first modern vessel to spend a full winter close to the North Pole—are aiming to fill in the gaps of knowledge.

Scientists are certain that the Arctic ice is disappearing. The shrinking ice cap accelerates warming globally. As Greenland and other Arctic glaciers lose ice, they help raise sea levels, potentially exposing millions of people to flooding. Nearly every dramatic, headline-grabbing effect of climate change, from alarming coastal erosion to intense and frequent fires, is already happening in the Arctic, at a fast pace and at a giant magnitude.

“These individual things are part of a very complex system that’s changing dramatically,” says Guido Grosse, head of the permafrost research unit at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Institute for Polar and Sea Research, or AWI. “Because it is very remote people have a hard time understanding how it might affect our life in more temperate regions. But it will.”

About a third of the size of the Christophe de Margerie gas tanker, the Polarstern is almost like a second home for polar scientists. The ship has been sailing Arctic and Antarctic waters for almost four decades. Spending months on the blue and white research vessel means sharing a tiny cabin with another scientist, sleeping in tight bunk beds and sipping infinite amounts of tea and coffee in the ship’s Red Saloon.

A satellite internet connection allows the researchers to communicate with loved ones on the mainland via Whatsapp. On the long winter days, Agatha Christie-style murder mystery games are organized to kill the hours. Friendships are forged–and broken—and the vessel’s sauna, gym and the small swimming pool become welcomed distractions. With no goals and multiple balls, scientists have invented a special discipline of water polo that only exists on the Polarstern.

The centuries-old quest to establish a northern navigation route that would connect Russia with Asian ports, the one taken by the Christophe de Margerie, helps illustrate the Arctic’s transformation. That route has long been a strategic priority for Russia, which accounts for over half of the total Arctic coastline.

The reason is obvious: The Northern Sea Route, stretching more than 3,000 nautical miles between the Barents Sea and the Bering Strait, provides a shortcut to Pacific ports. Shippers could send oil, gas and metals such as nickel and palladium to Asia more quickly, potentially shaving costs.

So far, Russia’s largest liquefied-gas producer, Novatek PJSC, and the nation’s largest private oil producer, Lukoil PJSC, send their eastbound cargoes via the route during summer.

The issue, of course, is that the Arctic waters are covered with ice nearly round the year, with only a few areas completely ice-free even in summer, a trend that has historically frustrated shippers and explorers alike.

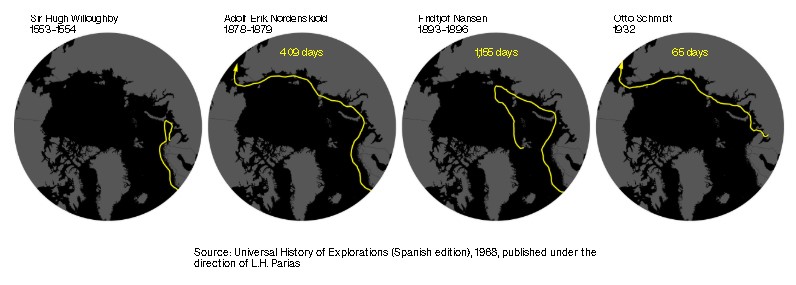

An Englishman named Sir Hugh Willoughby gave the route a shot in 1553. He described “very evil weather” and “terrible whirlwinds” as he attempted to find a northeastern passage. A year later, his diaries were found along with his frozen body and the rest of his crew on the Kola Bay, in a place he named “the heaven of death.”

The first to succeed in crossing was adventurer Adolf Erik Nordenskiold, who spent the winter months of 1878 and 1879 stuck in the ice aboard the Vega before finding his way. In 1932, Polar explorer Otto Schmidt on board Soviet icebreaker Alexander Sibiryakov completed the first ever uninterrupted voyage through the route, taking four summer months.

That got the attention of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. He created an authority, Glavsevmorput, and charged it with maintaining what is now known as the Northern Sea Route. By the turn of this century, traffic exploded as periods of ice-free conditions grew longer and longer.

Russian scientist Alexander Yulin recalls how only two or three decades ago the summer navigation period in the Russian Arctic lasted just 80 days a year. “Now, it’s 120, and most recently even as many as 150 days,” says Yulin, who runs the science lab that prepares ice outlooks for Russia’s state-owned Northern Sea Route Administration.

That may be conservative. A 2014 research paper from Kyoto University estimates that if navigation in the Northern Sea Route is extended to around 225 days per year, it may be economically viable to use the Arctic link during that entire period (with the Suez Canal used the remainder of the year).

These changes will prove a huge boon for Russia, which extracts almost 90% of its natural gas and more than 17% of its oil output from the Arctic zone. The region also contains around nearly all of Russia’s platinum and palladium reserves, and accounts for 97% of the nation’s nickel production.

Rosatom, the Russian state-owned nuclear corporation in charge of managing the route, is forecasting a big jump in shipments of these products through the Northern Sea Route. The company now navigates it, deploying nuclear icebreakers for nine months of the year. Ice-class vessels such as the Christophe de Margerie don’t need icebreakers in summer, though the early journeys this year did require assistance for part of the route. But Rosatom won’t wait for global warming to run its course. It’s looking at year-round navigation starting in 2025, with help from more powerful icebreakers.

Andrew Dale is a captain on another ice-class liquefied natural gas carrier that sailed the Arctic route this spring. His pictures posted on LinkedIn show calm water, blue skies and even a playful polar bear— nothing like harsh forces that doomed Sir Willoughby. “The salary doesn’t always just go into the bank,” Dale wrote in testament to the beautiful scenery. He also acknowledged that it had been one of the most challenging navigations in his career.

Scientists aboard the Polarstern are trying to better understand the mechanics driving that difference across the centuries. Their vessel sailed into Arctic currents last September, turned the engines off and began drifting toward the North Pole. Their task: to peer into the mass of its ice and snow and measure everything, from its atmosphere to its chemistry and ecosystem. The mission mirrors that of Norwegian explorer and scientist Fridtjof Nansen, who drifted north sailing on a wooden ship 127 years ago.

“Things that we will experience over the next couple of decades are already happening in the Arctic,” says Grosse, the AWI researcher, who, while not onboard this journey, has been to the Arctic dozens of times before on scientific missions.

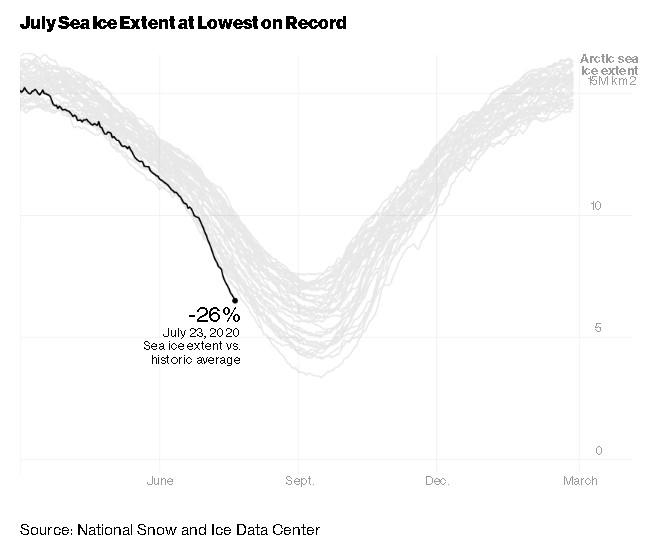

Most scientific models suggest that the first ice-free Arctic summer could happen around the middle of this century. There are more pessimistic forecasts suggesting total melting of the ice cap in summer could happen before, and optimistic outliers pointing to some time after 2100.

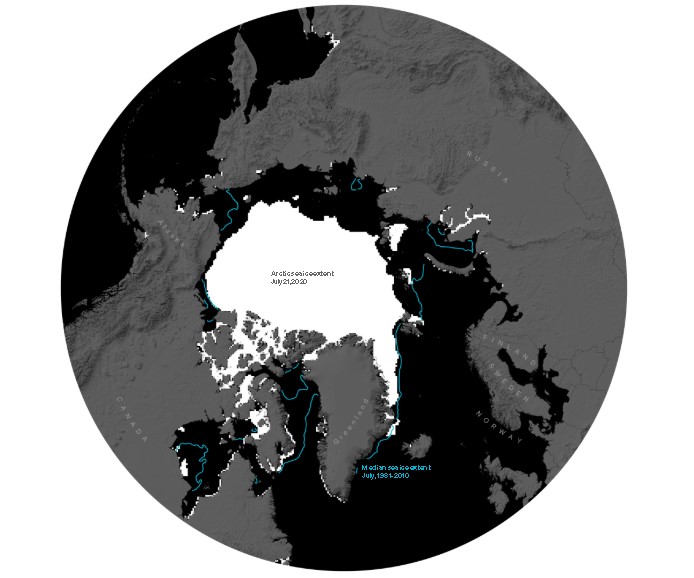

By the end of summer 2019, the Arctic ice cap had shrunk to the second-lowest level since satellite monitoring started in 1979. As of last week, on July 18, it was 26% lower than the historical average for the day. The Arctic is currently on track to record the lowest-ever ice coverage for the whole season. A study released in March estimated that the Arctic and Greenland lost ice during the 2010s at a rate six times greater than in the 1990s. That’s causing ocean levels to increase, leading some Arctic coastlines to lose as much as 50 meters to the sea annually.

It’s a scope and speed of change that doesn’t require scientific skills to observe. “Climate change is obvious,” says Vyacheslav Konoplev, 68, who has spent his life in the Arctic. “The ice is thawing and becoming thinner.” He now works at Russian miner Norilsk Nickel, managing a fleet shipping metal from the miner’s Arctic facilities to the northwestern port of Murmansk.

The Arctic is warming so fast that it has become an accelerator of climate change in the rest of the world. The white surface of the ice cap helps reflect sunlight back into space, effectively cooling the planet. When the ice melts, it’s replaced by ocean, which is dark and absorbs the light, heating up the sea surface.

“This affects oceanic and atmospheric circulation in the northern Atlantic, which has effects in faraway places like New York or Germany,” Grosse says.

The heat is speeding up the thawing of permafrost, the frozen ground that covers much of Russia’s Siberia, Alaska in the U.S. and the Yukon territories in Canada. When permafrost thaws, the organic matter that has been stored there since the ice age releases greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere.

Drier ground and high temperatures are also leading to seasonal fires that are starting earlier in the year, lasting longer and burning larger areas of land. Last year’s fire season was the worst in those terms, as well as in the amount of carbon dioxide emitted. This year the seasonal fires started even earlier and have so far released even more carbon dioxide.

Stefanie Arndt, a sea physicist at AWI in Germany, boarded mid-voyage in March as the leader of the ice team. A seasoned scientist, she had been on board the vessel seven times before. Yet this one was different, spending so much time in the ice and so close to the North Pole.

It didn’t start auspiciously. A landing strip built on the ice for emergency evacuations fell apart, trapping the scientists who were supposed to end their shift and return home by plane. But Arndt eventually made it home in June.

“When you compare the extent of the sea ice with previous decades you see that it is decreasing,” she says. Timing the exact moment when the Northern Sea Route will become ice-free is tough. “This decade or the next one,” Arndt says, “but it will come for sure.”