JEWS AT ZAGREB HOSPITAL DURING WWII

By: Ina Vukic

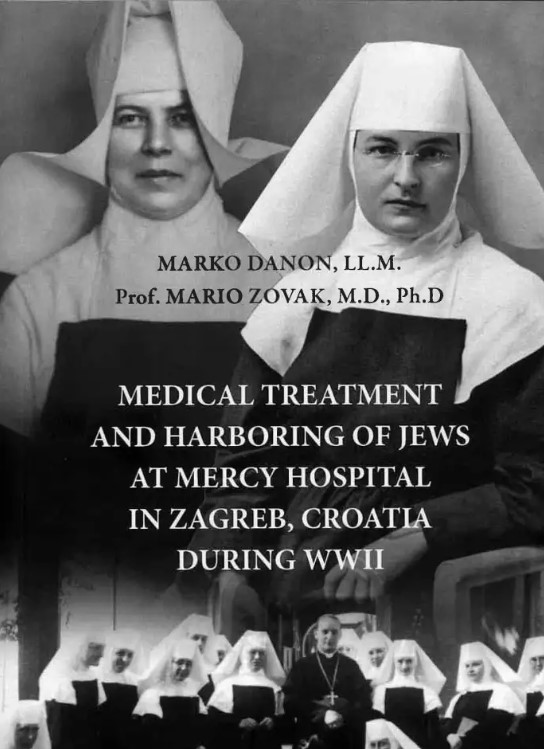

Photo: Center for Interreligious Understanding

MEDICAL TREATMENT AND HARBORING OF JEWS AT MERCY HOSPITAL IN ZAGREB, CROATIA DURING WWII

“Despite the indifference of most Europeans and the collaboration of others in the murder of Jews during the Holocaust, individuals in every European country and from all religious backgrounds risked their lives to help Jews. Rescue efforts ranged from the isolated actions of individuals to organized networks both small and large,” says on the Rescue page on the website of the Holocaust Encyclopaedia of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Even that page, despite it being encyclopaedic, gives us scanty and poor information on the rescue of Jews. When in May 2023 I discovered that a book about rescue of Jews in Croatia during World War II was released in the United States (published by Center for Interreligious Understanding, NJ) “Medical treatment and harboring of Jews at Mercy hospital in Zagreb, Croatia during WWII” by Marko Danon, LL.M. and Prof. Mario Zovak, M.D., Ph.D., I was so very gladdened. To the widest of extents our experience about remembering, writing, hearing, and reading about the Holocaust, seeking to be informed about it, is shaped by the encounter in the vast written, audio, and visual material available to us with the perpetrators of these World War Two atrocities and the victims being the focus and the content.

But what about those who rescued the Jews from such terrifying and cruel destinies? We do not hear or read much about the Jews that were saved in those times of the Holocaust or about rescue efforts. I often wondered if it was not purely, and unjustly, due to biased political motives that the rescue of Jews is discussed so little, and when it is, it appears as pinned with much less newsworthy coverage and relative lack of both public praise and interest.

Holocaust like any other major event in history and today, so colossally impacting humanity, must be looked at and discussed in its entirety; no bars raised, no victim ignored, no victim fabricated, no rescuer ignored, no rescuer fabricated, and no perpetrator spared.

To illustrate something of what I said above, the world I grew up in marvelled at the Hollywood 1993 production of the highly and worldwide acclaimed movie “The Schindler’s List”, based on the 1982 book by the Australian author Thomas Keneally “Schindler’s Ark”, the depicted the saving during World War Two of more than a thousand Jews, mainly Polish. The listings of individual people who saved Jews on the list of Righteous Among Nations, passed us and passes us by without much, if any, fanfare; on the other hand, the capture of a single person charged to have been a perpetrator of the Holocaust killings, attracts enormous media coverage, often yielding the feelings of joy and excitement – for justice’s sake! Whether the hunt for Nazi criminals mounted by, for instance, Simon Wiesenthal Center in past decades, with worldwide “front page” media coverage had created a membrane in our minds that prevents similar newsworthiness, joy, and excitement about discovering in research of those who rescued Jews is perhaps for others to say. Be it as it may, there seems to be almost a kind of a public conspiracy of silence against those who saved Jews. Barely a few of media outlets cover it. So, when in 2011 US-based historian Dr Esther Gitman published her book “When Courage Prevailed: The Rescue and Survival of Jews in the Independent State of Croatia 1941-1945”, that extensively revolves around her historical research findings, for which research she was the recipient of the prestigious Fulbright Scholarship, I was also very gladdened. Gladdened because it showed us of the several ways the rescue of Jews proceeded in those dangerous times and it showed us several individuals, including Croatia’s own Blessed Cardinal Alojzije Stepinac, who at their personal peril saved thousands of Jews.

The political efforts since World War Two included writing history about Croatia in World War Two did not include the rescue of Jews, but it included the perpetration of Holocaust crimes, too often “embellished” with fabricated numbers of victims and circumstances.

“This book would never have been published if l had not, when I collected some material, visited the manager of the ‘Sisters of Mercy Hospital,’ Prof. Dr. Mario Zovak says in the Introduction to the book ‘MEDICAL TREATMENT AND HARBORING OF JEWS AT MERCY HOSPITAL IN ZAGREB, CROATIA DURING WWII’. ‘After I told him that a lot of Jews were harbored and treated at the Hospital, which was managed by the Sisters of Mercy during World War II, the professor suggested that we set up a memorial at the Hospital containing the names of all the persons who were most deserving of it.

Many were suspicious, as they could not believe that there was a hospital in Zagreb during the Independent State of Croatia where 300 Jews were treated and hidden in World War II. Some Jews were admitted to the Hospital on several occasions. The NDH (Independent State of Croatia) laws provided for the death penalty for those who hid or otherwise helped the Jews… The research itself took a long time. There is no available data yet about Jews who died during the war and were buried in cemeteries, and there is also no official record of the persons buried in those cemeteries. Another problem is the Jews who survived the war, but did not return to Zagreb, and instead moved elsewhere, which is why it was very difficult to find and count them…”

This 90-page book by Marko Danon, LL.M. and Prof. Mario Zovak, M.D., Ph.D. represents a deeply valuable contribution to honouring those brave individuals who, to the real risk of their own peril, saved other human beings, Jews. It masterfully and credibly covers topics and matters that include the Zagreb Jewish Religious Community during WWII, the Mercy Hospital in Zagreb, Croatia during WWII, individual accounts by prominent Jews who were treated and hidden at Mercy Hospital during WWII and Jewish survival analysis. There is a wealth of genuine historical documents discovered that make this book even more compelling than any written text can yield. Further, the book provides the reader with a thorough insight into how the Nazis operated in Croatia after they occupied the country, and how the sisters of Mercy Hospital were unique in doing what they could to harbour Jews by listing them as patients, and caring for them, so that they could survive. We discover that here 309 Jews were saved by the Mercy sisters and with the full support and guidance that Blessed Cardinal Alojzije Stepinac provided for them.

Individual accounts of survival in the book includes: “Adela Fröhlich first stayed at Mercy Hospital from June 27 to July 27, 1942, and then again from March 14 to July 3, 1943 (when she felt she was safe from being deported). However, even after the May 1943 deportations, German intelligence services in the NDH complained that there were still Jews in Zagreb, and they could be regularly encountered in some coffee shops. In June of 1943, German intelligence compiled a list of 85 Jews throughout the NDH. Twenty-six of them lived in Zagreb, and among them was a certain “Frau Fröhlich. It is very likely that this referred to Adela Fröhlich who, while the Gestapo and Ustasha Police conducted searches, was staying in Mercy Hospital. When she received information that the police were intensely looking for her, she went to Mercy Hospital for a third time on November 4, 1943. To ensure her own safety, she remained in the hospital until the end of WWII; she spent 1.013 days in hospital,” pp 24 of the book.

“The presentation in this book is not emotional, but factual – simply stating facts, events of what happened and took place, and the simple description, item after item, name after name. This is so devastating that it cannot help but move the reader. Often, we speak of 6 million Jews in the same breath that we speak of thousands of others who were killed. But it is a totally different and devastating experience when you see the listing of those people who were saved; each name has a history; each name was a terrified person, not knowing whether they would live or not. What this book does is force us to view ourselves and examine the way we live our lives, and the values that are of utmost importance to us. Would we really have had the courage to silently, secretly, and with determination validate the sacredness of each individual life…” writes Rabbi Jack Bemporad, Director, Center for Interreligious Understanding, Teaneck, NJ and Rabbi, Congregation Micah of New Jersey, Cresskill, NJ in the Preface for this book.