NYT: A MOVIE ABOUT THE LEADER OF A SMALL BALKAN COUNTRY

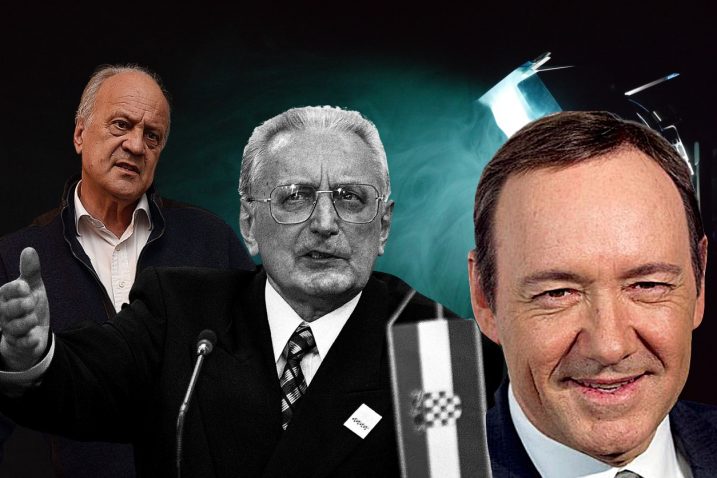

To Buff a Balkan Leader’s Image, a Filmmaker Calls In Kevin Spacey

A director cast the beleaguered actor as Franjo Tudjman, the late Croatian leader, whom some call a patriot and others revile as an ethnonationalist zealot.

By: Andrew Higgins

Photo: RTL

A hagiographic movie about the stiff former leader of a small Balkan country was never going to be a global box-office hit. But its director, a former water polo champion turned darling of right-wing Croatian cinema, found a novel way to generate some buzz: He cast Kevin Spacey as its star.

While Hollywood has generally turned its back on Mr. Spacey because of sexual assault accusations against him, purging the 63-year-old from its roster of bankable talent and deleting him from productions already in the works, a new cinematic tribute to a nationalist leader some view as a dangerous bigot puts the “House of Cards” star front and center.

The 90-minute film celebrates Croatia’s first president, the late Franjo Tudjman, a leader revered by fans as a Balkan George Washington but reviled by foes as an ethnonationalist zealot. The movie, “Once Upon a Time in Croatia,” goes into general release in Croatia in February and will be screened in other countries, including the United States.

The director, Jakov Sedlar, 70, conceded in an interview that in Croatia, many people, particularly the young, do not care much about Mr. Tudjman, a highly divisive authoritarian figure whom the historian Tony Judt described as “one of the more egregiously unattractive” leaders to emerge in the early 1990s from the rubble of Yugoslavia, of which Croatia was formerly a part.

Warren Zimmerman, who was the American ambassador to Yugoslavia as the multiethnic country unraveled, warned in a 1992 cable to Washington that Mr. Tudjman’s election as Croatia’s president in May 1990 had brought to power “a narrow-minded, crypto-racist regime” that, in tandem with Slobodan Milosevic of Serbia, was unleashing “nationalism, the Balkan killer.”

But having Mr. Spacey play Mr. Tudjman, the director said last week in Zagreb, the Croatian capital, “will definitely help” break through a wall of what is at best public indifference and at worst fierce hostility toward the man who led Croatia’s battle for independence.

“Ask people whether they have heard of Spacey or Tudjman, they will, of course, say Spacey,” he said. The American actor’s fame, no matter the risk of it curdling into infamy, and undisputed acting talent, Mr. Sedlar added, “will certainly attract people to see my film about Tudjman.”

The director declared that Mr. Tudjman, who died in 1999, “was not a nationalist, but a patriot, an absolutely positive personality.” And Mr. Spacey, a two-time Oscar winner and a friend of the director for more than a decade, “is the best of the best actors” and “absolutely innocent,” Mr. Sedlar said.

Both men, Mr. Sedlar says, have been unjustly maligned: Mr. Spacey by accusers like Anthony Rapp, a fellow actor whose battery claim against the disgraced star was thrown out in October by a New York civil court, and Mr. Tudjman by domestic political rivals and foreign critics angry over his role in the blood-soaked destruction of Yugoslavia.

One of seven states that emerged after the collapse of Yugoslavia, Croatia today is a stable democracy of fewer than four million people, a popular tourist destination and a global soccer power.

But the struggle to shape the history of the Yugoslav wars, critical to national identity in each of the countries spawned by the violence of the early 1990s, still rages across the region, particularly among filmmakers in Croatia, Serbia and Bosnia, the nations that saw the worst of the fighting.

“The history of the war is a constant process of remembering and forgetting,” said Dejan Jovic, a professor at the University of Zagreb. Memory wars, he added, are especially active in cinema. Each side, Mr. Jovic said, “remembers only what it wants and forgets the rest.”

Mr. Sedlar’s new film makes little effort to give a full and balanced history. It avoids any mention of crimes committed under Mr. Tudjman’s leadership, like attacks on Bosnian civilians, the ethnic cleansing of Croatia’s once large Serb minority and the destruction of a 16th-century bridge in the Bosnian city of Mostar in 1993. It skips his outreach to extreme nationalists linked during World War II to the Ustashe, a fascist group whose brutality shocked even some German Nazis.

But, the director insisted: “This is not propaganda. It is just my view.”

Croatia, almost ethnically homogeneous as a result of the 1990s violence that drove out many Serbs and members of other minorities, has mostly moved beyond the narrow ethnonationalism of Mr. Tudjman’s era and become a member of the European Union and NATO. While Mr. Sedlar has been promoting his movie, the government had been focusing on getting the country ready to adopt the euro and to enter the borderless Schengen zone, on Jan. 1.

The government, though led by the political party Mr. Tujdman founded, wanted nothing to do with Mr. Sedlar’s film and rebuffed his appeals for funding. The director said he raised the 400,000 euros needed — about $425,000 — from private donors.

He initially hoped to make a full-scale biopic to mark the centenary of the former Croatian president’s birth. But he settled for a more modest production built around Mr. Spacey’s reciting Mr. Tudjman’s stirring speeches.

The director said Mr. Spacey had taken the part out of friendship, and had neither asked for nor received any payment. Mr. Spacey’s lawyer, Jennifer L. Keller, did not respond to a request for comment.

Whether playing Mr. Tudjman will help Mr. Spacey in his quest for rehabilitation is another matter. It is not his first acting role since accusations against him surfaced in 2017 — he has appeared as a detective in an Italian feature and as a mysterious henchman in an American thriller — but his role as Mr. Tudjman is perhaps his riskiest.

Laura Silber, an author of “Yugoslavia: Death of a Nation,” said she was mystified that anyone would want to be associated with a tribute to the former Croatian leader. She had met him several times while covering the Yugoslav wars as a journalist and found him, she said, to be “repulsive” — an unashamed bigot with a “superiority complex” who “could not control his loathing for Muslims,” the largest ethnic group in neighboring Bosnia.

“He was like Dr. Strangelove meets Adolf Hitler,” she recalled.

Mr. Tudjman had fought against fascism during World War II, joining Communist partisans opposed to Hitler’s puppet regime. But in the 1990s, he refused to condemn the Ustashe legacy and decreed that independent Croatia should adopt a red-and-white checkerboard coat of arms that had been used by ethnic Croats for centuries but that closely resembles the Ustashe’s symbol.

Mr. Sedlar, who served for years as Mr. Tudjman’s cultural attaché in New York, comes across as a calm and reasonable man entirely free of the violent, often racist rhetoric that gave Croatian nationalism such a bad name. But he brooks no criticism of Mr. Tudjman.

“Compared with his establishment of an independent Croat nation, all the other stuff is absolutely unimportant,” Mr. Sedlar said, adding, “Without Tudjman, independent Croatia would not exist.”

Vesna Skare-Ozbolt, a fan of the former president who worked in his office as an adviser from 1991 until his death of cancer, insisted that while Mr. Tudjman, a former Communist general in the Yugoslav Army, had some unappealing personality traits, “He deserves a film.”

“He is the father of the nation,” she said. “He did a great job.”

Mr. Spacey’s performance in the film, which includes archival footage of Mr. Tudjman making wartime speeches in Croatian, consists largely of Mr. Spacey intoning the same speeches in English, walking through government buildings in white-soled sneakers and scribbling in a book.

Critics in Croatia have been divided along political lines in their reviews, though even hostile ones have praised Mr. Spacey’s performance.

One panned the film as “garbage” but described Mr. Spacey as “basically the best part of the movie,” adding, “He had a difficult task: to recite in English verbal sausages from Tudjman’s better-known speeches and give them a certain passion without any clear context.”

Despite his legal victory in New York, Mr. Spacey still faces serious legal troubles in Britain, where he is expected to stand trial this year on charges of sexual assault. He has pleaded not guilty.

The jury of history is still out on Mr. Tudjman, and Ms. Silber, the former war correspondent, said it was unlikely to reach a clear verdict any time soon, at least not in Croatia.

“He will never be judged by history in Croatia because he delivered their independence,” she said.